30 CCR5-delta32

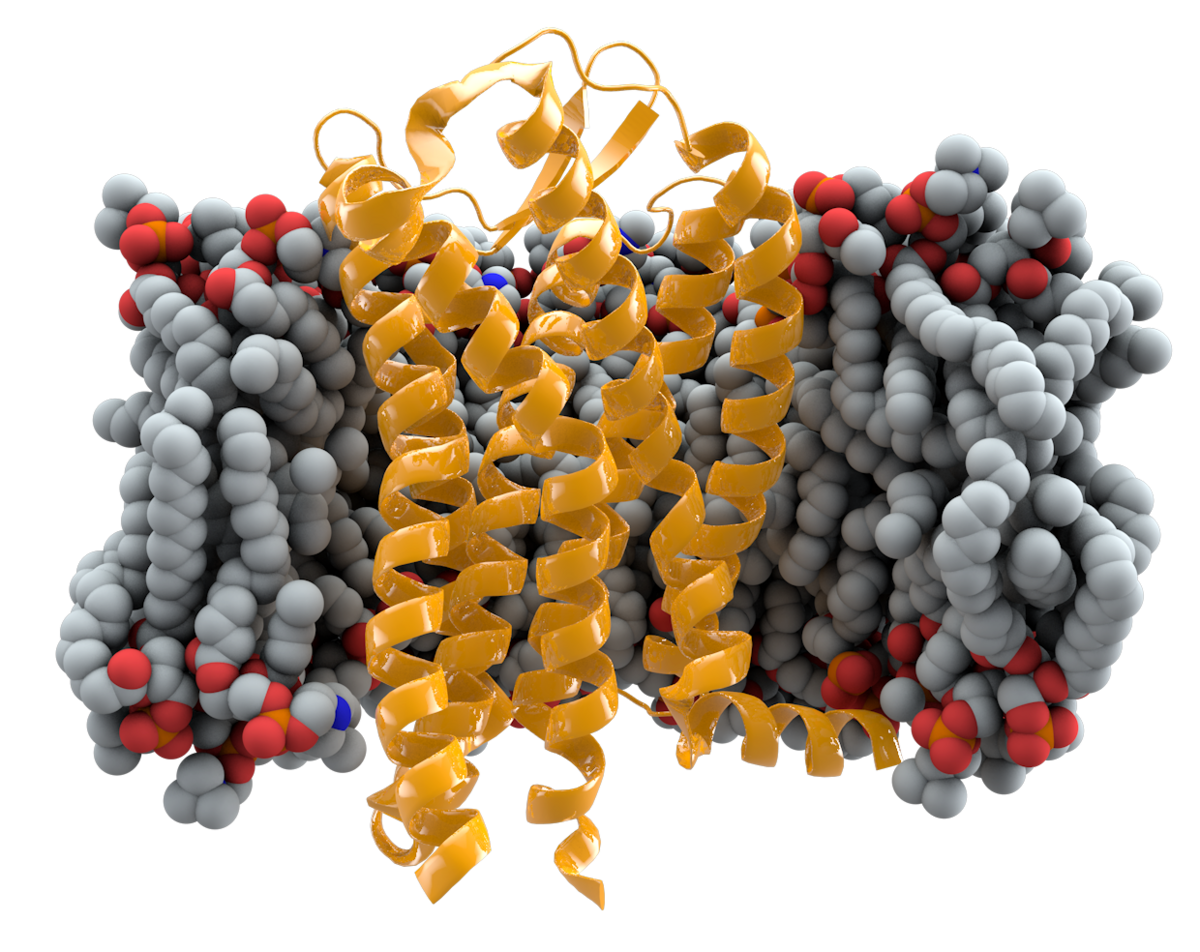

Human Immunodeficiency Virus targets immune cells

HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) infects immune cells by specifically targeting and binding to certain receptors on the surface of these cells. The primary immune cells that HIV infects are CD4+ T cells (commonly known as T-helper cells), macrophages, and dendritic cells. Here’s a simplified step-by-step explanation of how HIV infects immune cells: The first step in the infection process involves the attachment of HIV to immune cells. The virus carries a glycoprotein on its surface called gp120, which binds to the CD4 receptor on the surface of CD4+ T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells. This interaction is the initial binding event between the virus and the host cell. After binding to CD4, HIV also requires a co-receptor to gain entry into the host cell. Two common co-receptors used by the virus are CCR5 and CXCR4. Depending on the viral strain, it can use one or both of these co-receptors. This interaction between gp120 and the co-receptor triggers a conformational change in the virus, allowing it to fuse with the host cell membrane. The conformational change in the virus membrane allows it to fuse with the host cell membrane. This fusion event enables the virus to release its genetic material into the interior of the host cell. Once inside the host cell, HIV carries an enzyme called reverse transcriptase, which converts its single-stranded RNA genome into double-stranded DNA. This process is known as reverse transcription.

The newly formed viral DNA is transported into the cell’s nucleus, where it is integrated into the host cell’s DNA. The enzyme integrase plays a critical role in this step. Once integrated, the viral DNA becomes a permanent part of the host cell’s genetic material. The integrated viral DNA is transcribed into messenger RNA (mRNA), which is then translated by the host cell’s machinery to produce viral proteins and RNA. This leads to the assembly of new viral particles. New viral particles are assembled in the host cell and are released from the cell’s surface in a process known as budding. The new virus particles can go on to infect other immune cells and continue the cycle of infection. As HIV continues to infect and replicate within CD4+ T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells, the immune system’s response is compromised. Over time, the gradual loss of CD4+ T cells, which are crucial for coordinating the immune response, weakens the immune system’s ability to defend the body against various infections. This progressive immune system decline eventually leads to the clinical symptoms associated with AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome).

Can specific gene variants provide resistance to HIV?

The CCR5 gene and its protective variant, CCR5-delta32, thus play a pivotal role in the complex interplay between human genetics and HIV. The CCR5 gene, specifically its CCR5-delta32 mutation, has garnered significant attention in the field of HIV research due to its remarkable ability to confer a degree of natural resistance against the virus. The CCR5 gene, short for “C-C chemokine receptor type 5,” encodes a protein receptor found on the surface of certain immune cells, including T-cells and macrophages. This receptor acts as a gateway for HIV to enter these cells, a critical step in the virus’s infection cycle. However, a naturally occurring genetic variant of CCR5 known as CCR5-delta32 possesses a mutation that renders the receptor non-functional. Individuals who inherit two copies of this mutation are notably resistant to HIV infection, as the virus struggles to enter and infect their immune cells. This extraordinary genetic resistance has raised considerable interest in the scientific and medical communities, as it offers insights into potential HIV treatment strategies and the development of innovative therapies.

The frequency of the CCR5-delta32 variant varies significantly across different populations worldwide. It is important to note that historical factors, such as population migrations, genetic bottlenecks, and the prevalence of diseases like HIV, can influence the presence and distribution of this protective mutation. Here’s an overview of the frequency of the CCR5-delta32 mutation in different regions: The CCR5-delta32 mutation is most common in populations of Northern European descent, particularly in Scandinavia. In some regions of Northern Europe, such as Sweden and Finland, the mutation can be found in approximately 10-15% of the population. This high prevalence is thought to have resulted from strong selection pressures due to past epidemics, like the bubonic plague. As you move southward in Europe, the frequency of the CCR5-delta32 mutation decreases. In Southern European countries like Spain and Italy, the prevalence drops to about 5% or even lower. The CCR5-delta32 mutation is relatively rare in African, Asian, and Indigenous populations. In most cases, it occurs in less than 1% of these populations. The low frequency can be attributed to the historical lack of selective pressure from diseases like HIV in these regions.

Aim

Your goal is to use pairwise alignment to find the position of the delta32 mutation and establish if it is a deletion, insertion, or nucleotide substitution. This way, you, or other researchers, will be able to learn how the mutation changes the gene’s protein-coding sequence.

The learning goals of this exercise are:

- Acquire practical experience using online alignemnt tools.

- Understanding how parameters in the Needleman-Wunch algorithms affects the alignment.

- Understand the different uses of DNA and protein alignment.

- Acquire practical experience using online Blast to search an NCBI sequence database.

- Getting acquainted with different file formats for storing sequence information.

Preparation

Fasta sequence format

Files containing DNA or protein sequences are just text files formatted in a particular way so that each sequence can be associated with additional information. The most simple format is called FASTA format, and files with sequences in this format are called FASTA files and are usually given either a “.fa” or “.fasta” suffix. A FASTA has two elements for each sequence: a header line with a leading ” >” character followed by one or more lines with the DNA or protein sequence (the sequence may be broken over several lines). The content of a FASTA file with two (short) sequences in it could look like this:

>7423344 some additional description

AGTCCCTTGCA

TTATTGCAATAT

>2342134 some additional description

GGTCCAATTGC

AAATTGGAATAThe first word after the “>” in the header line is usually a sequence identifier; the rest is an additional description or information.

Aligning DNA sequences

For this this exercise, you will have four fasta files each with one sequence in it:

- The full mRNA of the normal CCR5 gene: CCR5_mRNA.fa

- The full mRNA of the CCR5-delta32 variant: CCR5_mRNA_delta32.fa

- The coding sequence (CDS) of CCR5: CCR5_CDS.fa

- The coding sequence (CDS) of CCR5-delta32: CCR5_CDS_delta32.fa

You can download the files on Brightspace.

Exercise 30-1

Before we head into the actual investigation, lets begin by looking at the exon/intron structure of CCR5 by aligning the mRNAs of CCR5 to its CDS using the Needleman-Wunsch algorithm. Go to the EBI website for pairwise alignment. Under “Sequence type” you need to select “DNA” to enable alignment parameters suitable for DNA alignment. Now align the two sequences by copy/pasting the mRNA into the top input field and the CDS into the bottom one (you must include the header line with the “>” character). Leave the rest of the options with their default values.

Guided Reflections

- What are the other default values? Click “more options” to see what they are.

- Which score matrix gap penalties are used?

- Does the program use linear or affine gap scoring?

- Are gaps at the ends of the alignment scored differently than the internal gaps?

Exercise 30-2

Now click “Submit”, to get your job queued on the server. Yol, and the bottom part shows parau have to wait a bit. When the job is completed and the output is shown, the lines beginning with “#” provide additional information about the alignment. The top part list the options used for running the “needle” program in the terminameter values and alignment statistics.

Guided Reflections

- What gap scoring was used?

- Which substitution matrix was used?

- Where do you find the result of the alignment?

- The alignment shows differences and similarities between the two sequences. Which differences do you see between the mRNA and the CDS? Why is there a difference?

Exercise 30-3

Now, on to the actual investigation. Begin by aligning the mRNAs of CCR5 and CCR5-delta32 to each other using the Needleman-Wunsch algorithm using the default values of parameters. Look at the alignment results.

Guided Reflections

- Describe the similarities between the two sequences. How many bases are the same and where are they located?

- Describe the differences between the two sequences. Where are the differences located on the mRNA and how many bases are involved? (Hint: 5’-UTR, 3’-UTR, Coding region)

Aligning protein sequences

Exercise 30-4

Now, you will translate the coding sequence of CCR5 and CCR5-delta32 to see which effect the mutation has on the protein level. Go to the Expasy translate website and set the “Output format” to “verbose”. Then, translate the two coding sequences, one at a time, by pasting the FASTA entries into the field (including the header line).

Guided Reflections

- What are the likely reading frames of each sequence? (number and direction)

- Which differences do you observe based on the translated sequence?

Exercise 30-5

Now go back to the EMBOSS Needle website and align the two protein sequences. Look at the results of the alignment.

Guided Reflections

- Where are the similarities between the two protein sequences?

- Where are the differences between the two protein sequences?

- How does the mutation affect the protein? (Hints: deletion, insertion, missense, nonsense, frameshift)

Searching a database using Blast

Sooty mangabay (Cercocebus atys) is a species of primates. Sooty mangabays also have common variants in their CCR5 gene that seem to protect them against SIV (simian immunodeficiency virus). We want to investigate how the Sooty mangabay CCR5 variants are similar or different to the gene variants found in the human CCR5.

Exercise 30-6

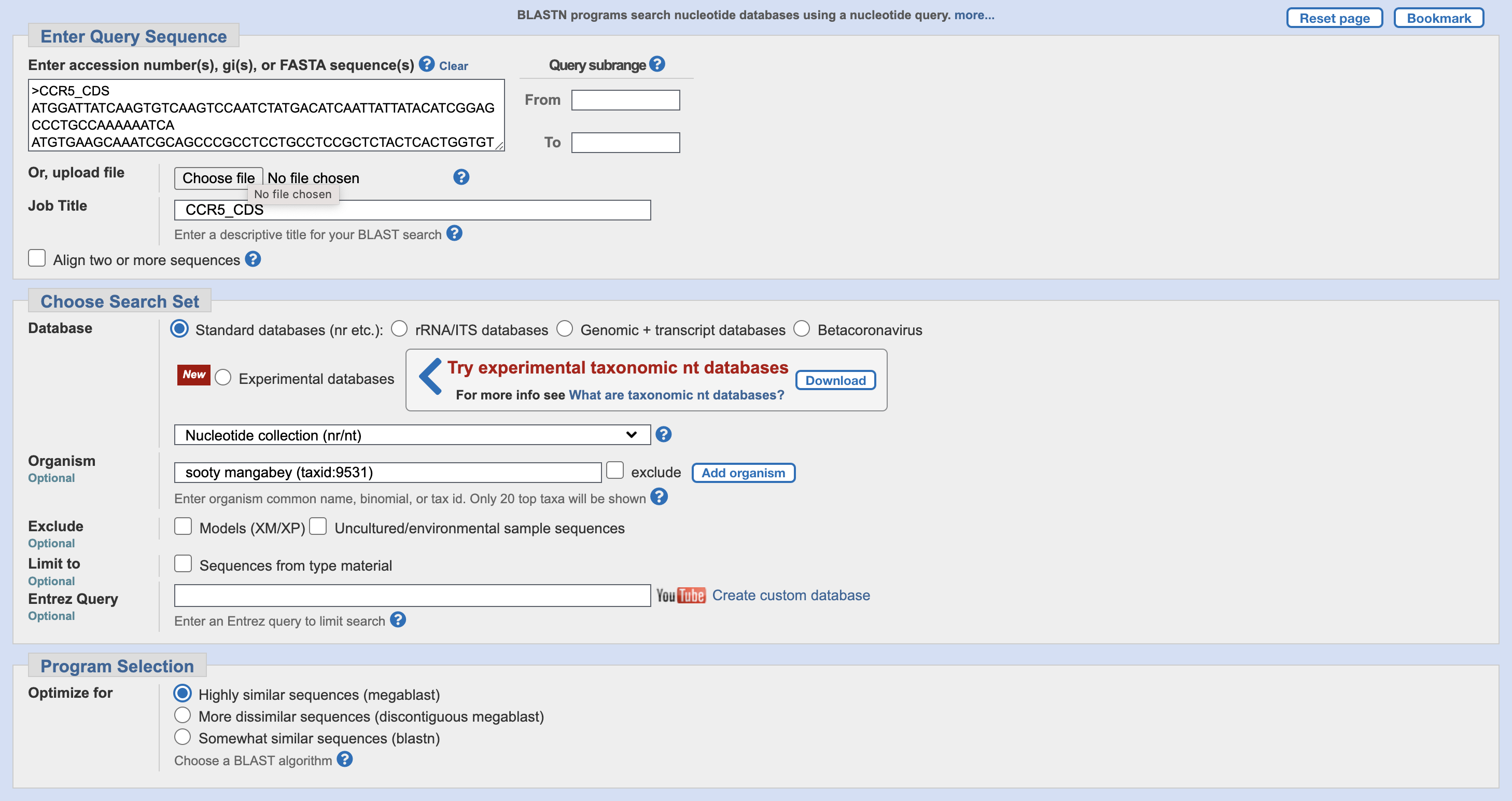

You can use Blast to find and investigate these sequences too. Go to the Blast website at NCBI. Clicking “Nucleotide BLAST” will take you to the search interface for the versions of Blast optimized for DNA and RNA searches. Leave the settings to their default values, but take a look around to see what options are available. “Program Selection” lists the version of Blast. We are using megablast for this.

Guided Reflections

- Click the “?” icon to learn a bit about each one. How do you think megablast and blastn may differ in the kmer sizes and thresholds they use?

Exercise 30-7

Before you start the database search, you want to limit its scope to only sequences from sooty mangabey. Set organism to sooty mangabey (“sooty mangabey (taxid:9531)”). Once you do this, it should look like Figure 30.1. Now paste in the CCR5 CDS and click the blue “BLAST” button at the bottom of the page to queue your search request (you may have to wait a bit).

Once the search results appear, they are sorted by E-value. The light blue header row lets you sort them by other criteria. “Query cover” sorts the database hits by how much of your search sequence (query) they cover.

Guided Reflections

- What does the E-value mean?

- What types of sequences does the BLAST search return?

Exercise 30-8

Since you are looking for search hits to a CDS in the other species, look for “C-C motif chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5), complete CDS” in the descriptions of search hits and pick the one with the highest percent identity. Clicking the corresponding link in the description column takes you to a local alignment of the part of your query sequence that aligns with the database sequence. In this case, it covers your entire CCR5 CDS.

Guided Reflections

- Describe the differences shown by the alignment. How many bases are different? How many gaps are there?

GenBank sequence format

Exercise 30-9

Now go back to the list of search hits by clicking the “Descriptions” link in the light blue bar above the alignment you were just looking at. See if you can find any search hits with names including “delta”. There should be a delta delta-24 allele among them. Pick the one with sequence ID AF079473.1. Inspect the alignment to the human CCR5.

Guided Reflections

- What characterizes these variants? What does the “delta” in the variant name refer to?

- Given what you now know about the human and mangabey CCR5 genes, do you expect that the delta32 mutation to have arisen before or after the common ancestor of humans and mangabeys?

Exercise 30-10

Go back to the descriptions list by clicking the “Descriptions” link in the light blue bar. On the left are tick boxes for each search hit. Mark only the two you have been looking at (IDs AF051905.1 and AF079473.1). In the “Download” dropdown list pick “GenBank” to download the two sequences in GenBank format. GenBank is a sequence entry format like Fasta, including much more information about each sequence. Open the downloaded file in VScode and see what it looks like.

Guided Reflections

- When were the sequences determined/published?

- What sequencing method was used?

- For each sequence, note another piece of information provided in the GenBank entry format.

Exercise 30-11

In the GenBank file, you can find the translated sequences of each CDS. Make a new text file in VScode and paste the two translated sequences in to create a Fasta file like this:

>normal

MDYQVSSPTYDIDYYTSEPCQKINVKQIAARLLPPLYSLVFIFG

… rest of the sequence …

>delta24

MDYQVSSPTYDIDYYTSEPCQKINVKQIAARLLPPLYSLVFIFG

… rest of the sequence … Now, head back to the EBI needle website and align the two protein sequences. Make sure it is set to protein this time.

Guided Reflections

- Where is the deletion located?

- Does it just delete amino acids, and if so, how many, or does it change the reading frame or induce stop codons?

- How does the mangabey CCR5 mutation compare to that in humans?

Putting it all together

Exercise 30-12

Have a look at this scientific paper: “A Novel CCR5 Mutation Common in Sooty Mangabeys Reveals SIVsmm Infection of CCR5-Null Natural Hosts and Efficient Alternative Coreceptor Use In Vivo” and look at Figure 1 and its figure legend.

Guided Reflections

- Figure 1A shows the alignment of 6 different gene variants. What species are they from and what variants are shown?

- Figure 1B shows the alignment of the predicted protein sequence. What do the grey boxes mean? What do the arrows mean? What does the highlighted sequence mean?

- We have now looked at the sequences of different mutations. Suggest an experimental method/setup, that might show something about the functional importance of the mutations.

Project files

Download the files you need for this project:

https://munch-group.org/bioinformatics/supplementary/project_files