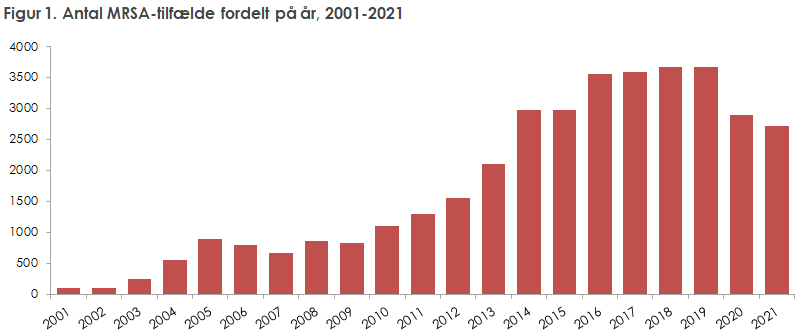

31 MRSA

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a strain of the staph bacteria that’s become resistant to the antibiotics typically used to treat ordinary staph infections. Originally, the Staphylococcus aureus bacterium was a common cause of skin infections, pneumonia, and other medical conditions. However, its methicillin-resistant counterpart, MRSA, emerged as a strain that resists many of the conventional antibiotics. This resistance is not limited to just methicillin but extends to other antibiotics, often rendering standard treatments ineffective.

Individuals infected with MRSA can experience a range of ailments, from skin and wound infections to more severe conditions like pneumonia, bloodstream infections, and sepsis. Particularly concerning is its ability to cause life-threatening complications in older or immunocompromised people or people with chronic illnesses.

A critical factor that has amplified MRSA’s resilience and adaptability is the phenomenon of horizontal gene transfer (HGT). Unlike the usual vertical transfer of genes from parent to offspring, HGT facilitates the direct exchange of genetic material between different bacterial species. This form of gene transfer has been pivotal in the rapid acquisition and spread of antibiotic resistance genes within microbial communities, including those of Staphylococcus aureus.

The most common mechanism of HGT involves direct cell-to-cell contact, where a donor bacterium transfers genetic material, like the SCCmec carrying the mecA gene, to a recipient bacterium. Less commonly, viruses that infect bacteria, known as bacteriophages, can mistakenly package bacterial DNA, including resistance genes, and transfer them to another bacterium upon subsequent infection.

MRSA’s resilience stems from various genetic mutations but is prominently due to the acquisition of the mecA gene. This gene provides the bacteria with the ability to produce a unique protein that alters its cell wall, reducing the efficacy of even last-resort antibiotics, such as methicillin. mecA is believed to have been acquired through HGT and often locates to a mobile genetic element called the staphylococcal chromosomal cassette (SCCmec), allowing for its potential transfer between different strains or even species of bacteria.

Given the role of HGT in the rapid spread of resistance, it’s evident that MRSA’s evolution isn’t merely a product of its internal genetic changes. It’s deeply intertwined with a broader microbial ecosystem, where genes, particularly those conferring survival advantages like antibiotic resistance, can be exchanged, adopted, and propagated. This understanding underscores the challenge that antibiotic resistance presents.

Iinvestigating the origins of the mecA gene in MRSA providesinsights into the potential sources and the evolutionary trajectory of antibiotic resistance. Your goal is to identify which organism(s) Staphylococcus aureus might have acquired the mecA gene, and what evidence supports this potential horizontal gene transfer event?

The structural learning goals of this exercise are:

- Learn how to retrieve sequences for analysis

- Build practical experience using Blast

- Acquire practical experience with multiple alignment tools.

Sequence Retrieval

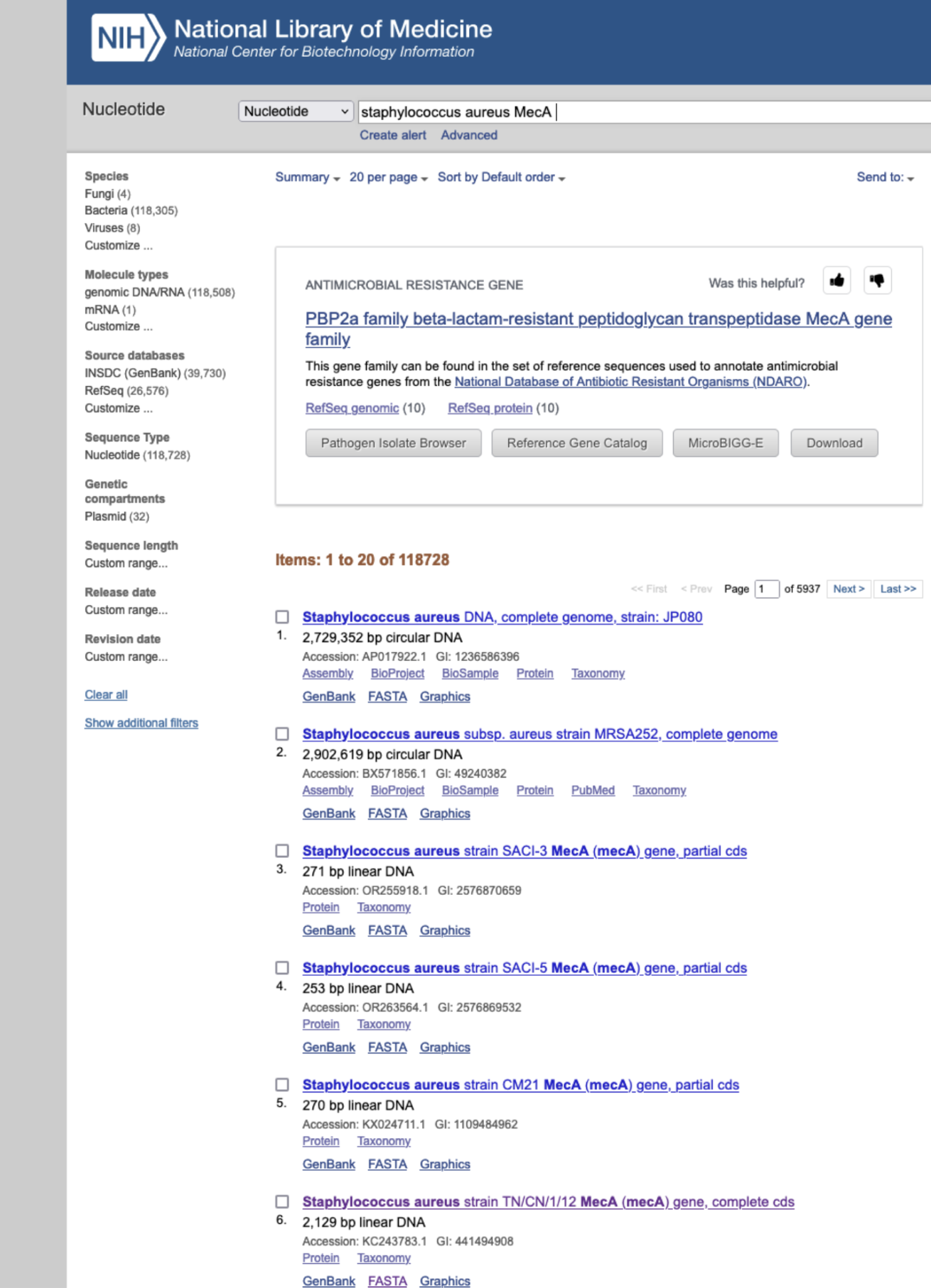

Exercise 31-1

Obtain the genetic sequence for the mecA gene from MRSA. Go to Genbank and find a complete sequence for mecA in Staphylococcus aureus. That is, do a nucleotide search for “Staphylococcus aureus mecA” and select a MecA gene version with “complete cds”. See Figure 31.2. Do not pick the complete genome. Check if MRSA is mentioned in the documentation for the result.

Exercise 31-2

Find the FASTA version of the genomic reference assembly. This will give you the genetic sequence of the gene. Keep the header of the sequence (“>… Staph…, complete cds”), as we will need this later.

Exericse 31-3

Find the FASTA version of the protein sequence. There might be a link to this in “Related Information.”

Database Searching using BLAST

Exercise 31-4

Go to the NCBI BLAST web portal. Use the mecA nucleotide sequence to search for similar sequences in the nucleotide database. Which organisms have regions with high similarity to the mecA gene nucleotide sequence in your query? Tip: Check the “Show results in a new window” to allow searching multiple times and compare results. Further, know that it is normal for blasting to take a few minutes. Examine the following metrics (columns):

- E-value (Expect value): The number of hits one can “expect” to see by chance when searching a database of a particular size. Lower E-values indicate a more significant match. Typically, E-values below 0.05 or especially 0.01 suggest a significant match, but the threshold can depend on the content and especially the size of the search. The longer a search term, the less likely it is for random matches.

- Percent Identity: The percentage of identical matches between the query and subject sequences over the aligned region.

Exercise 31-5

Try adjusting the number of maximum target sequences in “Algorithm Parameters” (e.g., to 1000). You can also exclude “Staphylococcus aureus” from the search results to only see other organisms.

- How did this affect the results?

- Check the taxonomy of your found organisms.

- Check the graphic summary of the results.

Exercise 31-6

Try the other programs (“Program Selection”). They may be slower but can find less similar matches that may uncover the potential sources of the gene.

- Did this affect the results? If so, how? (Use the taxonomy and graphic summary in your analysis.)

- What are the main differences between the programs (megablast, discontiguous megablast, and blastn).

- What do we expect from the different algorithms? It is okay to use Wikipedia or similar resources.

Exercise 31-7

Try the protein blast algorithms and compare the findings. This requires the protein sequence. Do you find the MecA gene product (i.e., protein) in other types of bacteria (i.e., not Staphylococcus strains)? If so, what may this imply about horizontal gene transfer of this gene? Is there a risk of MRSA “helping” completely different, and perhaps more dangerous, bacteria genera become antibiotics resistant?

Exercise 31-8

You might see multiple Staphylococcus strains when allowing higher maximum target sequences. What are the potential interpretations of this concerning horizontal gene transfer? Can we deduce a single origin of the gene in Staphylococcus aureus from these results? Remember that we see a snapshot of where the genes were present during various studies – this is ever-changing.

Exericse 31-9

According to Bloemendaal et al. (2010): “Methicillin Resistance Transfer from Staphylococcus epidermidis to Methicillin-Susceptible Staphylococcus aureus in a Patient during Antibiotic Therapy”, mecA may be transferred from Staphylococcus epidermidis. The mecA gene is located on the Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome mec (SCCmec), and they found that the SCCmec were almost identical in MRSA and in S. epidermidis in a patient.

- Does your results imply this may be true?

- If this was the case in that one patient, does it mean the MecA gene in MRSA always stems from S. epidermidis?

Multiple Sequence Alignment using ClustalW

Exercise 31-10

Choose five or more types of bacteria from your BLAST results, such as Staphylococcus epidermidis (include Staphylococcus aureus). You will be comparing the MecA gene’s sequence in each of these to find relations between them.

Exercise 31-11

Go to Genbank and find nucleotide sequences for the MecA gene in each of your selected organisms. E.g., search for “Staphylococcus epidermidis MecA”. You should get the (when possible) complete sequence for the gene only. Get the header of the FASTA file as well.

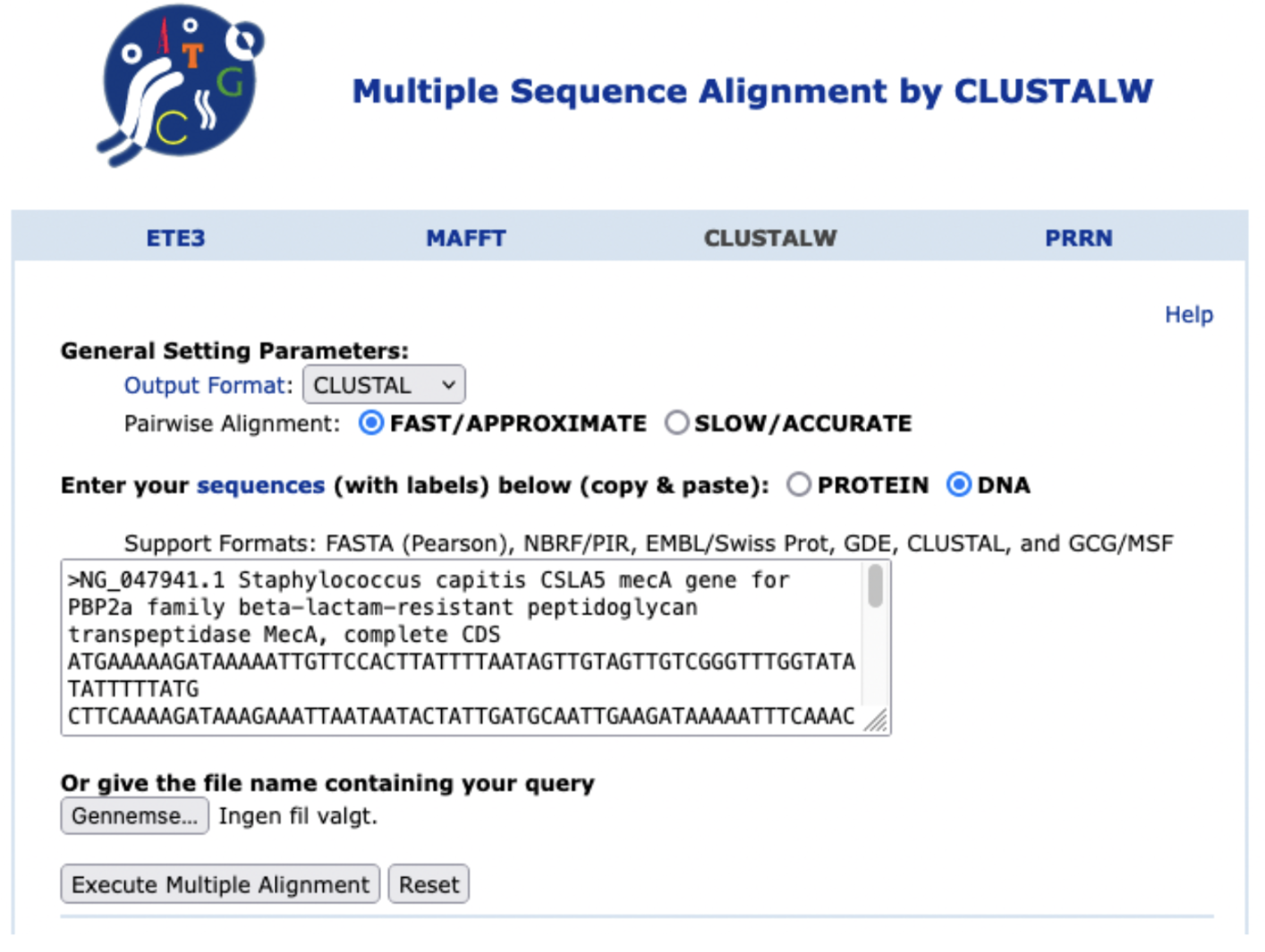

Exericise 31-12

Go to ClustalW at https://www.genome.jp/tools-bin/clustalw and input the sequences (with header first) of the mecA sequences from MRSA and the selected organisms. See Figure 31.3 Select DNA as you’re inputting nucleotide sequences. Feel free to try the protein sequences.

Run the multiple alignments. - What does the output tell us? - How may these alignments be useful to us in determining the origin of the MecA gene?

Exercise 31-13

At the top of the output page, select a method in the tree menu (e.g., FastTree) and press Exec. This will generate a phylogram. A phylogram is a depiction of evolutionary relationships between taxa, in this case, the mecA gene from different types of bacteria. The branch lengths illustrate evolutionary distance and nodes from where the tree branches can be interpreted as common ancestors when we are working with vertical gene transfer. Try to imagine what the nodes could be interpreted as when we are talking about horizontal gene transfer. Hint: maybe the nodes could be interpreted as possible horizontal gene transfer events.

- What does the generated phylogram tell you?

- How could we use phylograms to track the potential horizontal gene transfer between the different bacteria?

Discussion

Based on the BLAST and ClustalW results, which organisms might have been the potential source(s) for the mecA gene in MRSA?

- Discuss evidence of potential horizontal gene transfer events based on sequence similarity.

- Reason about the roles of the various HGT approaches in MRSA (i.e., Conjugation, Transduction, Transformation). What types are most likely between staph bacteria?

- Discuss the significance of horizontal gene transfer in the rapid emergence of antibiotic resistance.

- What are some ways we can use sequence alignments of MRSA to combat them? E.g., treatment, outbreak management (like tracking sources, spread, and evolution), and new drugs such as protein-targeting vaccines.

Additional tools

DTU (Technical University of Denmark) has developed a set of tools highly relevant to antibiotic resistance and MRSE specifically. These are not part of the assignment, but check them out if you are curious: